One of the common ways in which the human mind reacts to an unpleasant reality, such as the diagnosis of an incurable disease, is by denying it. Denial is usually not a conscious deliberate response, but a spontaneous, instinctive one, that ranks as a major hurdle in patient-care.

Last week, an anxious young mother brought her 13 years old only daughter to consult for a problem of chronic dysentery for four years. She had been passing frequent stools containing fresh blood and mucus, for which she had knocked on several pediatricians, taken several antibiotics, and finally reached a gastroenterologist who had diagnosed chronic ulcerative colitisafter colonoscopy examination. He had explained that the disease was caused by disordered immunity, did not have a short, simple, cure, and required prolonged medications (5-amino-salicylates, 5ASA) that he had prescribed.

Despite her getting better on 5ASA, they stopped her medications after a month, triggering relapse. The family could not believe how such a disease that required medications for years, could afflict their adorable daughter at such a tender age! They could not come to terms with the “incurable” nature of the disease and went into a “denial” mode.

Denial made them consult several doctors and many practitioners of alternative systems of medicine, for a permanent cure, but with no improvement. The cycle of remission with 5ASA, premature stopping of medications, relapse, restarting of 5ASA, improvement, stopping again after a month, continued till the girl became anemic, weak and miserable.

Denial is seen frequently in relatives and patients of cancer, chronic neurologic disorders and psychiatric ailments.

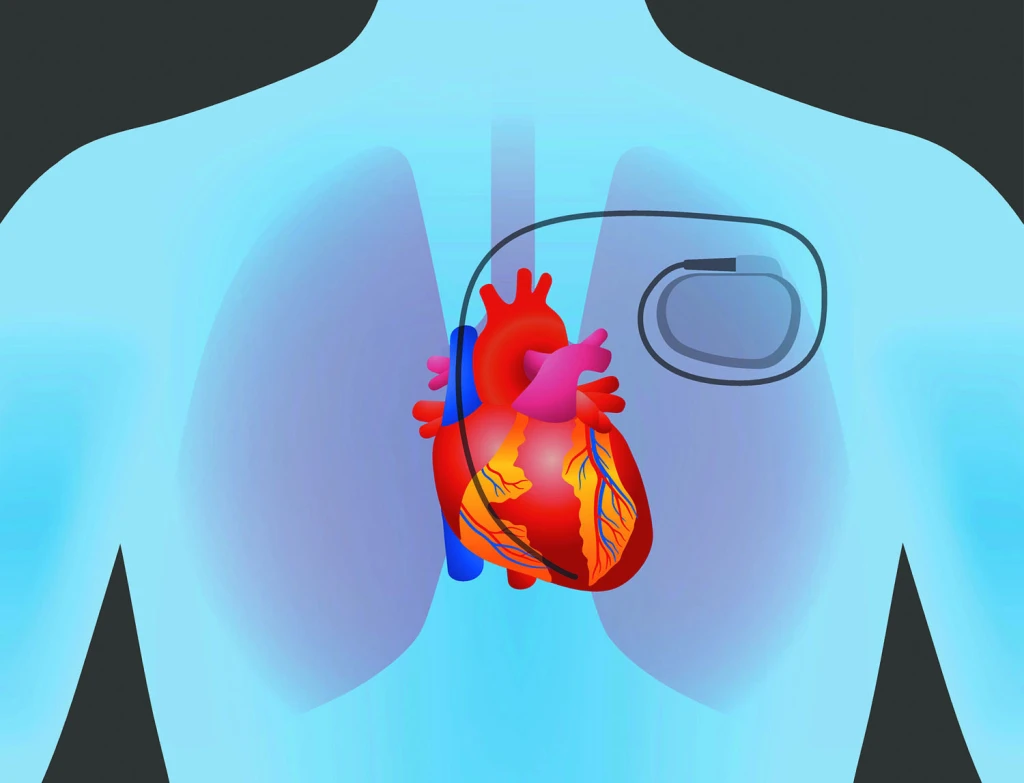

Depression is another common condition. A once-active vibrant 64 year old senior executive who used to be the toast of every board-room meeting, TV interview and party during his working years, recently began to feel his confidence and wit slipping away, to be replaced by fear and negative thoughts, imprisoning him to his bedroom.Like many ‘strong’ men, he refused to accept depressionas the diagnosis. To him the word meant ‘a mental illness that happened only to others who were weak’. The family joined the chorus with, ‘how can depression affect a person who has always been so full of life?’

And then began the ‘Dance of Denial’ with multiple medical opinions, many expensive investigations, frequent changing of medicines and the familiarlament “doctors are unable to catch the disease, tests are failing to pick up anything, medicines are being given as experiments without a clear confirmation by any investigation, and his condition is worsening day by day’. Depression unfortunately does not lend itself to detection by a blood test or scan. If he had stuck to the prescribed anti-depressant medications, he could have had the imbalance of serotonin in his brain restored, cut short his dark days and bounced back to good quality of life in a few weeks.

Depression is after all more common than we think. One in every three of us is estimated to suffer it at least one in our life-time, and one in seven of us is likely to have it severe enough to require treatment.

Unpleasant reality is difficult to accept and tackle, and the mind devises its own way to deny it. It occasionally helps, in a doomed person with advanced cancer, for example, allowing him to remain cheerful till death. But for most, it becomes an impediment to treatment and care.